A Durable Yet Vulnerable Eden in Amazonia

By ANDREW C. REVKIN

A new study has found that Yasuní National Park in Ecuador, which sits atop major oil reserves, is home to the most diverse array of plants and animals in South America and possibly the planet. (One resident is the Ecuadorean poison frog, seen above transporting its tadpoles; image by Bejat McCracken).

The study, “Global Conservation Significance of Ecuador’s Yasuní National Park,” published in the journal PLoS One, was undertaken by a large group of Ecuadorean, American and European biologists who, in printed statements, gushed about the explosion of life in the area. “This study convincingly demonstrates that Yasuní is the most diverse area in South America, and possibly the world,” said Anthony Di Fiore, an author who is a primatologist at New York University.

The authors noted that one area, the 1,600-acre Tiputini Biodiversity Station, on the northern edge of the park, has unparalleled peaks of diversity in reptiles, amphibians, insects, birds and bats.

The authors, a mix of academic researchers and scientists for environmental groups, recommended that a moratorium on new oil exploration or development projects within the park, which sits atop substantial reserves. Of particular importance, they wrote, is the remote and relatively untouched northeast corner.

The Ecuadorean government has been promoting a plan, the Yasuní-ITT Initiative, which would leave the park’s largest oil reserves permanently undeveloped. That project, however, hinges on as-yet uncertain flows of hundreds of millions of dollars from other countries to compensate for keeping the oil in the ground.

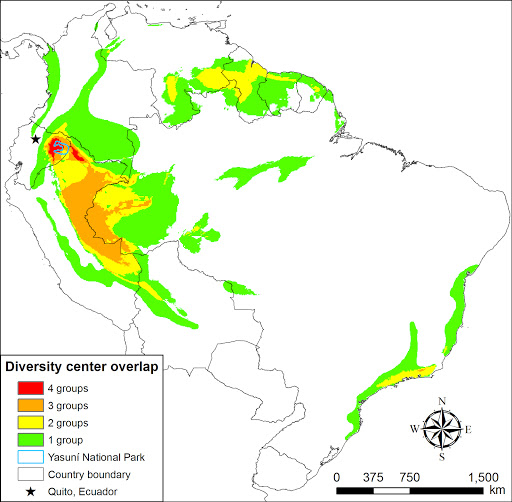

This map from the paper shows how the park, outlined in blue, sits at the conjunction of areas of peak biological diversity in for groups — amphibians, birds, mammals and vascular plants:

There are hints that the park could have extra conservation value in a warming world. Yadvinder Malhi, an ecologist at Oxford specializing in the Amazon, said that nearly all climate models simulating the impacts of global warming show the area staying wet even as other parts of the vast basin get drier.

“The simple fact is that the moist air passing over the Amazon converges and gets deflected by the Andes here, and that squeezes out moisture and produces rainfall like squeezing a sponge,” Dr. Malhi said in an email message.

Dr. Malhi and several other biologists familiar with the study said that the high biological diversity in Yasuní, in itself, hints that the area functioned as a moist refuge for life through past climate shifts that saw much of Amazonia shift to drier forest.

“The concentration of species in this area is likely to have held up over long periods – think tens of millions of years,” said Stuart Pimm, a specialist in tropical ecology at Duke University. “And wet places have more species than dry ones. I’d put my money on this being wet for a long term.”

Daniel Nepstad, an Amazon specialist at the Woods Hole Research Center, said the seeming durability of the ecosystem was no reason to relax about global warming.

“Even if an area remains wet doesn’t mean that it will be protected from the other aspects of climate change: rising and far more erratic air temperatures, higher rates of evaporation (evapotranspiration), and the rising concentration of CO2,” he said in an e-mail message. “It is misleading to imply that there are any ecosystems in the world that will not suffer profound change, and for many that change has already begun.”

No comments:

Post a Comment